Synopsis

A promising young Buddhist monk, Hsing-che, is serving under Master Liu-kuan. Master Liu-kuan specializes in the Diamond Sutra, which says that there’s no difference between dreams and reality.

One day, Master Liu-kuan asks Hsing-che to pay his respects to the Dragon King. Hsing-che goes to the Dragon King’s palace and gets drunk despite the fact that monks aren’t supposed to drink. On his way back he jumps into a lake to try to sober up, but bumps into eight fairies who are relaxing by the lake after paying their respects to Master Liu-kuan. He flirts with them before returning, very late, to the temple.

Upon returning, Hsing-che tries to meditate but keeps on thinking about the fairies. His attempt to meditate is interrupted when he gets called before his master, who is furious and somehow knows everything that’s happened. His master sends him to the underworld to be judged, where he is sentenced to be reborn as punishment. Meanwhile, the same thing has happened to the eight fairies, who somehow got caught flirting with Hsing-che.

The rest of the novel is about the nine of them finding each other in their next lives after being reborn. Since their rebirths were a punishment, this part of the novel naturally involves a lot of pain and suf—actually, no.

Hsing-che, reborn as Shao-yu, ends up getting everything anyone could conceivably desire. He comes first place in the state exams, is second only to the emperor in political power, and is rich and handsome. Oh, and he repeatedly has sex with the fairies and other beautiful women, sometimes more than one at a time, and all eight fairies end up becoming his wives or concubines. You’d think that this might at least lead to some conflict among the wives and concubines, but it doesn’t. Everyone is completely happy with this arrangement, Shao-yu most of all.

Shao-yu eventually retires, and a few years later decides to become a monk. Then he wakes up as Hsing-che, back in the old Buddhist temple, and is soon joined by the eight fairies, who have becomes nuns. Master Liu-kuan appoints Hsing-che as his successor, and after some time Hsing-che and the eight fairies become bodhisattvas and enter, together, into paradise.

|

|---|

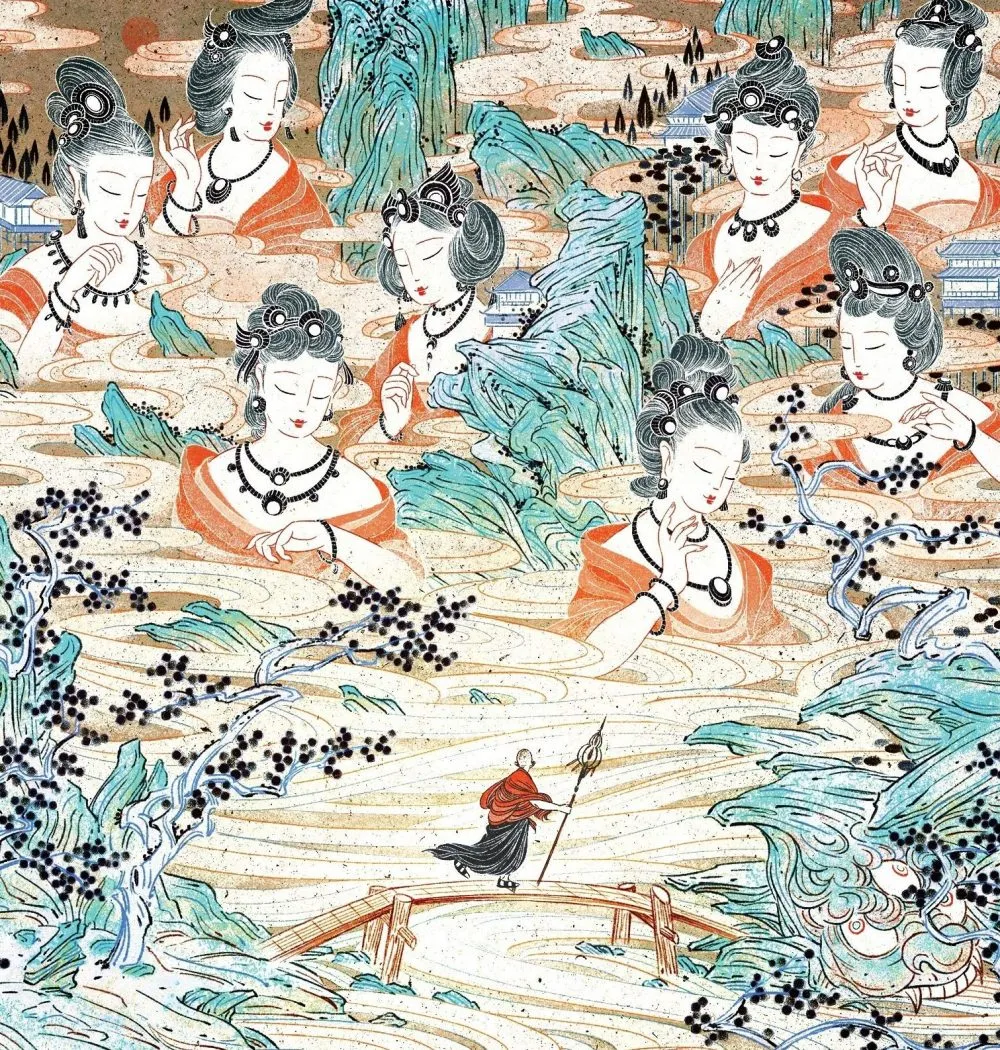

| Cover art by Feifei Ruan |

So, like, what is going on with this novel? Professional reviews generally speak of it as if it’s a Buddhist morality tale. And the novel does repeatedly highlight the main idea of the Diamond Sutra, that there is no difference between dreams and reality. In addition to the dreamlike start and end to Hsing-che’s reincarnation, the novel describes humans being confused with fairies and ghosts, boys pretending to be girls, girls pretending to be boys, time advancing suddenly like in a dream, and so on. So there is one Buddhist idea that the novel at least illustrates.

But I think this misses how startlingly anti-Buddhist the rest novel is. I’ll focus on three main anti-Buddhist themes in it.

Themes

Uselessness of meditation

The novel says that “the great purpose of Buddhism [is] to tame the mind and the heart”. But in the case of Hsing-che, it’s completely failed to achieve this purpose. After being reborn as Shao-yu, he lives a life almost comically dominated by sex, drunkenness, and the pursuit of power.

And it’s not like Hsing-che is just some random Buddhist. He spent a decade in a monastery studying under a great master whose name literally means “Master of the Six Temptations”. We’re told that Hsing-che is his best student out of hundreds, and everyone expects him to be made his master’s successor. If at the end of all this meditation and study Hsing-che is still fantasizing about a lifetime of sex with fairies, it doesn’t look like meditation and study are very helpful in “tam[ing] the mind and the heart”.

In the end, Shao-yu’s desires do fade and he awakes again as Hsing-che. But that’s not because of Buddhist meditation or study, which there is no mention of him doing as Shao-yu. It’s because he spent an entire lifetime having sex with whoever he wanted. The moral of the story seems to be the anti-Buddhist moral of The Picture of Dorian Grey: “The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”

Irrelevance of karma

Shao-yu often attributes his happiness to karma. But he is wrong, since he has bad karma and was sentenced to be reborn in the first place only as a punishment for violating his religious vows. The repeated mentions of karma just serve to highlight that in the novel’s universe, karma doesn’t impact the quality of your later lives, and those who confidently attribute outcomes to it have no idea what they’re talking about.1

Nihilist consequences of Buddhist metaphysics

There are two separate occasions on which Shao-yu has sex with creatures who are not fully human, or who he believes are not fully human. One he believes (incorrectly, it turns out) to be a “hungry ghost”, and so by having sex with her he believes he is having sex with an animated corpse. The other is a half-fish who has the power to transform into a full human, but Shao-yu doesn’t want to wait for that and has sex with her while she is still a half-fish.

In both cases the creatures appear to be a little grossed out on Shao-yu’s behalf. For example, before having sex with him for a second time, the supposed hungry ghost asks him, “How could I dare to embrace you again with this rotting corpse?”

This is where Buddhist teachings come to the rescue. Shao-yu responds by quoting the Buddha:

The Buddha said a man’s body is a transitory illusion, like foam on the water or flower petals in a gust of wind…Who can say, then, what really exists and what does not?

To reiterate, this is to justify having sex with what he believes to be a rotting corpse.

This is particularity striking because Buddhist texts sometimes compare humans to corpses in order to quell people’s desire for sex. For example, the Bodhicaryāvatāra encourages you to think of someone you sexually desire as merely a “cage of bones bound by sinew” and a “moving corpse” (chapter VIII, verses 52 and 70). Shao-yu turns this on its head, saying in effect: I agree that these two things are alike, but I choose to revise my opinion of corpses instead of my opinion of humans.

The more general point this is getting at is that Buddhist metaphysics doesn’t necessarily have the practical consequences that Buddhists take it to have. If life is just a “transitory illusion”, then why does it matter whether Shao-yu is having sex with a human or with a corpse? Why does anything really matter? Why shouldn’t you just have a good time? Isn’t that what you would try to do in an actual dream, and wouldn’t that be OK? So how seriously do Buddhists really take the idea that life is just a “transitory illusion”?

Appendix: What does the Diamond Sutra actually say?

The Diamond Sutra has two main themes. The first is, roughly, that there is no difference between dreams and reality, as summed up in this famous passage from it:

All things conditioned

are like dreams, illusions, bubbles, shadows

like dewdrops, like a flash of lightning,

and thus shall we perceive them.2

In other translations I’ve seen “compounded” instead of “conditioned”. This passage is a little more nuanced than my earlier glosses on it. Two obvious questions are (1) What does it mean for something to be conditioned? and (2) In what respects are conditioned things supposed to be like the given examples (dreams, illusions, and so on)? A third obvious question is (3) Why should we believe this?

As best I can tell, something counts as “conditioned” if it is non-fundamental. On this understanding, the vast majority of things are conditioned: you, me, tables, Greek yogurt, the metric system, and so on. The only unconditioned things are those at the fundamental level—maybe quarks or some more fundamental particles that we don’t yet know about. In the sutra itself, it’s clear that persons, living beings, sounds, smells, and tastes, among other things count as conditioned, which fits this interpretation.

As for (2), the given examples have a few distinctive qualities, though no quality is an obviously good fit for all of them. The examples are variously:

- short-lived (dreams, bubbles, dewdrops, flashes of lightning, maybe shadows)

- “immaterial” in some sense (dreams, illusions, shadows, maybe lightning)

- mind-dependent (dreams, illusions)

- “unreal” in some sense (dreams, illusions)

So the Diamond Sutra is claiming that all conditioned things have some or all of the above qualities.

As for (3), why we should believe this, the Diamond Sutra is silent. That’s unfortunate, since on its face it seems obviously false. For example, our best science says that the Sun (which counts as “conditioned”) has existed for around 4.6 billion years. That is not short-lived by any stretch of the imagination. And since the Sun exited before we did, it definitely isn’t dependent on our minds. Is the Diamond Sutra denying this? If so, it would be nice to know why.

So much for the first theme. The second main theme of the Diamond Sutra is that the Diamond Sutra is great and you are great if you study it. Here’s one representative passage:

The Lord said, “…[I]f there were as many world-systems as there would be grains of sand in those Ganges Rivers, and some woman or man were to fill them with the seven treasures and make a gift of them to the Realized, Worthy and Perfectly Awakened Ones…would that woman or man generate a lot of merit on that basis?”

Subhūti said, “A lot, Lord, a lot, Blessed One….”

The Lord said, “If, however, someone were to fill that many world-systems with the seven treasures and make a gift of them, Subhūti, and if someone were to do no more than learn just a four-lined verse from this round of teachings and teach it to others, the latter would generate from that a lot more merit, an immeasurable and incalculable amount.

It goes on like this. By my count, 25% of the Diamond Sutra (8 of 32 sections) is devoted to some form of self-praise or an attempt to express an absurdly large number that represents how much merit you’ll get if you study it.

Complication: The Diamond Sutra promises all those who study even four verses of it “an immeasurable and incalculable amount” of merit (§11). So maybe Shao-yu does have good karma, despite the fact that his master was trying to punish him. But this just highlights the strangeness of that teaching. Does it mean that if you study the Diamond Sutra, you can murder a thousand people and still have a good rebirth? It’s like a cheat code for infinite karma. ↩︎

When I took a Buddhist philosophy class at a local monastery, the monk recited this passage in an opening prayer before every class. ↩︎